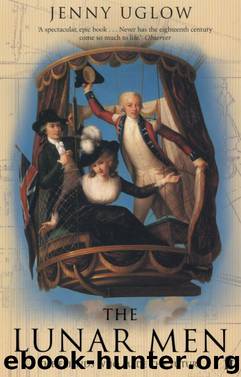

The Lunar Men by Jenny Uglow

Author:Jenny Uglow [Jenny Uglow]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780571266678

Publisher: Faber & Faber

Published: 2010-07-26T16:00:00+00:00

The more Darwin thought upon this, the more convinced he became.

*

Flowers, plants and their families, however, were different from rocks, gases, engines. They had always been part of the artistic culture as much as the agricultural and the medical, and – as many Linnaean names acknowledged – they were connected with myth, poetry, painting, embroidery and love. They were decorative, and they were feminine.

Botany was often considered the one scientific pursuit suitable for women, yet Linnaeus seemed rather shocking for a female audience. When he organized plants into class, order, genus, species and varieties he chose sexuality as the key, classifying flowering plants by the stamens, the male ‘genitals’. He grouped them into twenty-three classes, which were then divided into orders by the structure of the stigmas, the female ‘genitals’, while the supporting structure, the calyx, became the ‘nuptial bed’. This meant, of course, that some flowers had far more than a single male sharing a bed with the female – and the sexual naming went further, with some structures compared to labia minora and majora, let alone a whole class of flowers named Clitoria. There was no escaping the link between Linnaean botany and sex. Even the fungi, mosses and ferns, which have no flowering parts, were labelled the Cryptogamia, ‘plants that marry secretly’. In Britain, several botanists reacted with horror to the sexual emphasis and William Withering was certainly embarrassed. In his Botanical Arrangement, rather bizarrely, he changed ‘stamen’ to ‘chive’ and ‘pistil’ to ‘pointal’ for fear of offending the ladies. Darwin had little time for such linguistic niceties: for the translation of ‘pedunculis axillaxilus’ (taken from axillus, armpit), he offered ‘Flower-Stems in the angles’, commenting impatiently, ‘Surely in the angles will be as intelligible as armpit, or Groin, or any other Delicate idea.’14 But although they might not have acknowledged it, the botanical studies of both Withering and Darwin were linked to physical desire. Withering began by collecting flowers for Helena, and Darwin was now increasingly involved with a woman who was not only a passionate gardener, but whom he addressed in a deluge of intensely emotional pastoral verse.

His return to poetry was partly prompted by his second son, Erasmus. Suddenly he seemed to realize that his boys were growing up. At the start of 1775, Charles was sixteen, and Erasmus a year younger. They were like the two sides of Darwin’s personality: Charles brilliant, scientific-minded, outgoing and ambitious; Erasmus literary and sensitive. In March 1775 Charles went to Christ Church, Oxford, leaving after a year (to Darwin’s delight) and transferring to Edinburgh to study medicine. It was said that Darwin found his quiet second son Erasmus effeminate and irritating, but it was partly with him in mind that he founded a small literary circle in Lichfield. This included, of course, Anna Seward, as well as Edgeworth and Day when they were there, the poetry-writing squire Francis Mundy and the Rousseauian Brooke Boothby, leisured, indolent and frequently drunk. Revelling in his role as mentor, Darwin began versifying again.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Belgium | France |

| Germany | Great Britain |

| Greenland | Italy |

| Netherlands | Romania |

| Scandinavia |

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(4111)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4109)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(3851)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(3642)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3518)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3459)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3262)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3066)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(2843)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(2735)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(2722)

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Thatcher Margaret(2687)

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley by Alison Weir(2679)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(2649)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(2610)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2467)

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell(2396)

The One Memory of Flora Banks by Emily Barr(2349)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2267)